For S., with thanks

Last night, more than 50 comrades gathered to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the passing of a mate and comrade.

That mate was Comrade Alex, who was shot and killed on the Cooper Pedy opal fields on April 14, 1982.

Alex was one of the first of our generation of youthful Marxist-Leninists who, in the late 1960’s, rallied to the call of the Party and united to fight capitalism and imperialism.

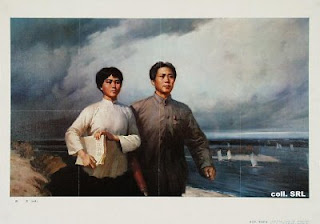

Alex stood out. For a start, he was a tall bloke (first from right in photo above, looking at camera), but his presence went beyond his height. He could light up a room with his dry sense of humour, his famous one-liners and ascerbic wit.

Alex was a practical bloke and made the smoke bombs for demos, handing out recipes for molotovs and generally looking for ways to push the envelope against the coppers. If they were there taking photos of marchers, Alex was there taking photos of them.

One of the coppers who specialised in harassing young left-wing opponents of the US imperialist war of aggression against Vietnam was "Curly" Marshall. "Curly" wasn’t big for a copper, but he let us know that he was on our tail night and day, often brushing past us in a pub and asking casually about something we had said or done the previous day.

One of those at the commemoration recalled how he had been helping Alex with an offset printer one day when "Curly" and another Special Branch copper arrived and started niggling Alex, trying to bait him into saying or doing something to warrant an arrest. For over half an hour this kept up, with Alex keeping his cool throughout, defusing their antagonism with his humour until they left.

When the situation was in his favour, Alex wasn’t quite the gentleman as far as the cops went. A number of them wore bruises that corresponded to the shape of Alex’s big knuckles after having rashly waded into lines of anti-war demonstrators.

Unfortunately for Alex, he was very much influenced by one particular friend who had a dominant personality and a tendency to commit a few too many political mistakes. One of those mistakes was not taking the women’s movement seriously. But there were other major errors on this friend’s part too. The straw that broke the camel’s back was when the friend arrived a day late for a conference of the Worker-Student Alliance, entered disruptively, refused to heed warnings of the Chair, and responded to a female comrade with "I think you might find the dictatorship of the proletariat a bit too physical". In the end it was decided that the friend and Alex should be expelled from a particular organisation which expected a higher level of discipline and understanding. To the friend, this was water off a duck’s back; to Alex, it was devastating. He had not thought that silly behaviour could carry such consequences, and he wept as the decision was delivered.

Within WSA, it was only the friend who was expelled. Alex bounced back and continued to make his valuable contributions to the revolutionary socialist movement.

However, it was clear that Alex was a marked man in Adelaide and that the cops would make it difficult for him to keep a job and provide for the family that he was building.

So Alex left for Cooper Pedy, a frontier town in the outback where law and order was pretty much provided by the miners themselves.

Alex had some success and started building a small business. Despite the remoteness of Cooper Pedy from Adelaide, Alex remained devoted to the cause of the people. I remember when WSA members at the big Chrysler plant in Adelaide were involved in a rank and file dispute with the management. There had been a strike, an occupation, and several arrests. Alex sent down two thousand dollars to the rank and file to help see them through the dispute, a characteristically selfless act of genuine commitment.

Those of us who met yesterday to remember Alex – and there were some from interstate and overseas – did so with great love and respect for the man.

He died too young in a lawless town.

He left a gap in all of our lives, and it was fitting that Henry Lawson’s poem "The Glass on the Bar" should have been read in his memory:

Three bushmen one morning rode up to an inn,

And one of them called for the drinks with a grin;

They’d only returned from a trip to the North,

And, eager to greet them, the landlord came forth.

He absently poured out a glass of Three Star,

And set down that drink with the rest on the bar.

"There, that is for Harry," he said, "and it’s queer,

‘Tis the very same glass that he drank from last year;

His name’s on the glass, you can read it like print,

He scratched it himself with an old piece of flint;

I remember his drink – it was always Three Star" –

And the landlord looked out through the door of the bar.

He looked at the horses, and counted but three:

"You were always together - where’s Harry?" cried he.

Oh, sadly they looked at the glass as they said,

"You may put it away, for our old mate is dead;"

But one, gazing out o’er the ridges afar,

Said, "We owe him a shout – leave the glass on the bar.

They thought of the far-away grave on the plain,

They thought of the comrade who came not again,

They lifted their glasses, and sadly they said:

"We drink to the name of the mate who is dead."

And the sunlight streamed in, and a light like a star

Seemed to glow in the depth of the glass on the bar.

And still in that shanty a tumbler is seen,

It stands by the clock, ever polished and clean;

And often the strangers will read as they pass

The name of a bushman engraved on the glass;

And though on the shelf but a dozen there are,

That glass never stands with the rest on the bar.

1889