For the moment, let us just note that the Bank of International Settlements has recently reported that global outstanding derivatives have reached 1.14 quadrillion dollars. Most of which doesn’t exist. It’s fictitious. And most of it is in the process of getting wiped out – written off as bad debt. To hell with it too, except that somewhere back along the food chain there are certain assets that this fictitious capital claims some connection with, and that’s why one of my friends said he lost $300,000 from his superannuation fund last year. Others report similar losses.

Let’s look at some fundamental questions of the capitalist economy.

Lenin characterized imperialism as the highest stage of capitalism, as capitalism in its decadent, moribund final phase.

It was that stage of capitalism in which finance capital, which had arisen from the merger of industrial and bank capital, had created a financial oligarchy within the bourgeoisie. These finance capitalists had assumed the leading role, the strongest and loudest voice among the component parts of the capitalist class.

The export of capital from the centres of advanced industrial production to the colonial periphery had played the major part “in creating the international network of dependence on and connections of finance capital” (All quotes from Lenin are from Section 3, “Finance Capital and the Financial Oligarchy” in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism.)

The publication of Lenin’s work was a creative development of Marxism, drawing together all the threads and all the newly developing phenomena in the capitalist economies since Marx’s theoretical studies of the “laws of motion of modern capitalism” in his 3-volume Capital. In the final volume of that work, Marx had noted that the endless pursuit of the accumulation of capital had accelerated the usurious and speculative practices by bankers and financiers on the stock market. The tendency for the rate of profit to fall in conventional industries created an attraction for the owners of finance capital to speculate in financial markets. There had already been precursors to today’s sub-prime crisis and credit crash, for example the South Sea Bubble of 1720, and Marx was well aware that such speculations caused fictitious capital to be created and destroyed in great cycles of financial melt-down.

By Lenin’s time, the concentration of production in great monopolies was accompanied by a growing separation of banking and industrial capital from finance capital. Today, the term “real economy” is still used to refer to that part of the productive process associated with the manufacture and sale of goods and services, as opposed to the speculative and parasitic world of the financiers.

Lenin wrote, “It is characteristic of capitalism in general that the ownership of capital is separated from the application of capital to production, that money capital is separated from industrial or productive capital, and that the rentier who lives entirely on income obtained from money capital, is separated from the entrepreneur and from all who are directly concerned in the management of capital. Imperialism, or the domination of finance capital, is that highest stage of capitalism in which this separation reaches vast proportions. The supremacy of finance capital over all other forms of capital means the predominance of the rentier and of the financial oligarchy; it means that a small number of financially “powerful” states stand out among all the rest. The extent to which this process is going on may be judged from the statistics on emissions, i.e., the issue of all kinds of securities.”

In fact Lenin was only touching the surface of what would emerge from the creativity of the “best and brightest” of this financial oligarchy. He might never have guessed how limited and infantile his phrase “all kinds of securities” might appear from the vantage point of the 1970s and onwards.

A finance vocabulary has come into existence since the 1970s that would have sounded like gobbledegook to an earlier generation of economists. Structured investment vehicles (SIVs) collateralised debt obligations (CDOs), CDOs of CDOs, credit default swaps (CDS), hedge funds, private equity firms, funds of funds, and so it goes on.

Just what are derivatives? According to Ellen Brown, author of the book Web of Debt, “Until recently, most people had never even heard of derivatives; but in terms of money traded, these investments represent the biggest financial market in the world. Derivatives are financial instruments that have no intrinsic value but derive their value from something else. Basically, they are just bets. You can "hedge your bet" that something you own will go up by placing a side bet that it will go down. "Hedge funds" hedge bets in the derivatives market. Bets can be placed on anything, from the price of tea in China to the movements of specific markets.”

In other words, unlike investments in the “real economy”, derivatives create nothing but the demand from banks for extensions of vast of amounts of credit that constitute fictitious amounts of capital.

The scale of this fictitious capital is almost beyond our ability to see how big it really is.

The Gross Domestic Product of all the countries in the world prior to the current collapse stood at about $US60 trillion. The amount gambled in the big derivatives casino stands at $US1.1 quadrillion. Given that a quadrillion is 1000 trillion we can start to appreciate the fantastic (as in “fantasy”, “not based in reality”) scale of this speculative and parasitic overproduction of finance capital.

To really “see” the scale of this fraud we’ll use the following graphics sourced from here (they are bigger and easier to see in the original).

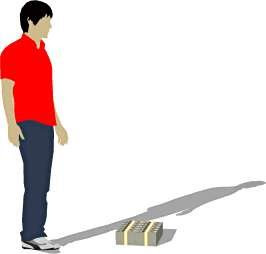

We start with a $US100 bill.

One hundred of these is half an inch thick and can fit in your pocket. That’s $US10,000.

One hundred packets of these could comfortably fit into a backpack. That’s $US1 million.

One hundred of these would fit onto a standard-sized pallet ($US100 million)...

...and ten pallets would represent 1000 million dollars, or $US1 billion.

A trillion is one thousand billion, so we multiply our ten pallets one thousand times…and it's getting hard to see our human figure at the bottom left hand corner of the pallets, now double-stacked to keep within the frame.

You’ll have to do the next bit yourself. A quadrillion is one thousand times the last image.

And don’t forget, our unit of measurement was a $US100 note, so we’d need one hundred lots of our quadrillion to see what a quadrillion $US1 notes look like!

And all of this money has created nothing (but non-existent values of itself) and will collapse back to nothing unless the banks and financial institutions that have underwritten this gambling idiocy are bailed out by taxpayers.

"Too big to collapse?" You bet! (It's a safer bet than derivatives trading!)

Lenin was unaware of the potential for the overproduction of finance capital (ie the creation of fictitious capital) on this scale through derivatives trading, but he was aware that in the imperialist era, it would be this sector of capital that would require the whole of society to pay for its speculations. He wrote, “Finance capital, concentrated in a few hands and exercising a virtual monopoly, exacts enormous and ever-increasing profits from the floating of companies, issue of stock, state loans, etc., strengthens the domination of the financial oligarchy and levies tribute upon the whole of society for the benefit of monopolists” (emphasis added).

At the moment a social-democratic wind has emerged in the aftermath of the super typhoon of the credit collapse prompted by the sub-prime crisis. Australia’s Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd has written a lengthy piece attacking neo-liberalism and declaring that “Not for the first time in history, the international challenge for social democrats is to save capitalism from itself” (The Monthly, February 2009). US Democrats President Barak Obama states, “We need not choose between a chaotic and unforgiving capitalism and an oppressive government-run economy” (Global Viewpoint, March 2009).

Suddenly it is fashionable for servants of capitalism to talk like socialists, even if it’s for the purpose of further service to capitalism and the capitalists!

Our task is to rebuild the revolutionary movement of anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist elements under working class direction and leadership and to create a sustainable, collective, planned and regulated economy that meets the needs of the people.