Progressive singer-songwriter Shane Howard is releasing his new album Goanna Dreaming this month, touring nationally from July 2.

For South Australians, Shane can be seen on Saturday 18 September 2010 at the Singing Gallery at McLaren Vale and on Sunday 19 September at the Church of the Trinity on Goodwood Road, Clarence Park.

The first bars of the album’s opening track, Earth Is Singing, slowly unfold from Howard’s intimate acoustic guitar and the Mexican Jarana of Francisco Gonzales, (one of the founding members of Los Lobos), building to a Goanna-esque rockin’, celebratory, crescendo. The song tells the back story of Howard’s first pilgrimage, all those years ago, to Uluru when he wrote the Australian classic, Solid Rock.

The first bars of the album’s opening track, Earth Is Singing, slowly unfold from Howard’s intimate acoustic guitar and the Mexican Jarana of Francisco Gonzales, (one of the founding members of Los Lobos), building to a Goanna-esque rockin’, celebratory, crescendo. The song tells the back story of Howard’s first pilgrimage, all those years ago, to Uluru when he wrote the Australian classic, Solid Rock.However, the song that has caught my interest is the rollicking Clancey & Dooley & Don McLeod which retells the remarkable, hidden story of Australia’s Black Eureka, when 800 Aboriginal pastoral workers, in Western Australia's Pilbara region, walked off the pastoral stations in 1946 and went on strike for pay and better conditions and gave birth to Australia’s contemporary Aboriginal resistance movement.

Here is how Shane Howard describes those events in the booklet accompanying the CD:

CLANCEY & DOOLEY & DON McLEOD

The Western Australian Aboriginal Pastoral Workers Strike of 1946

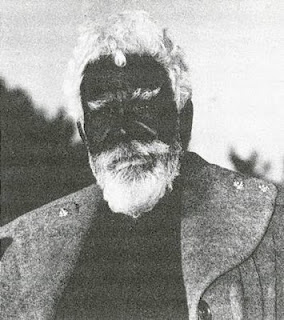

In 1942, on the western side of the Pilbara, Western Australia, a great meeting of the Aboriginal desert law men was organised by Dooley Bin Bin and Clancey McKenna (below).

Over 200 people attended, some travelling thousands of kilometres, from as far away as Halls Creek, Darwin and Alice Springs. There, at Skull Springs, they sat in council to discuss the shameful conditions that their people were living under, all through that central and western desert country. The meeting lasted for six weeks. There were 23 languages spoken and 16 interpreters.

Over 200 people attended, some travelling thousands of kilometres, from as far away as Halls Creek, Darwin and Alice Springs. There, at Skull Springs, they sat in council to discuss the shameful conditions that their people were living under, all through that central and western desert country. The meeting lasted for six weeks. There were 23 languages spoken and 16 interpreters.

One whitefella, the prospector Don Mcleod (above), was invited to that meeting. McLeod was one of the first whitefella’s to be born in Marble Bar, one of the most remote towns in Australia. He’d been invited because of the help he’d once given an Aboriginal elder who needed to be taken to hospital. None of the whitefellas at the time would help to transport him, but McLeod took him as a matter of course and thought nothing more of it. His empathy was noted and as a result he was summoned to attend the great desert council.

The people discussed what they could do to improve the future for their children. Work and iiving conditions were appalling for all Aboriginal people at the time but in the Pilbara, being so remote, it was particularly harsh and ‘out of sight and out of mind’. Aboriginal people were under the Native Administration Act and they were slaves in their own country. No wages, no housing, no freedom of movement and meagre rations. McLeod was appointed executor and the group became known as The Mob.

The people waited until the World War II ended, but on 1 May 1946, 800 Aboriginal workers went on strike and walked off sheep stations in the north-west of Western Australia. Under the guidance of McLeod, Bin Bin (left) and McKenna, the strike was well organised and initially stunned the authorities. All three were arrested and jailed and persecuted. Although the strike effectively lasted for at least three years, it never officially ended.

The people waited until the World War II ended, but on 1 May 1946, 800 Aboriginal workers went on strike and walked off sheep stations in the north-west of Western Australia. Under the guidance of McLeod, Bin Bin (left) and McKenna, the strike was well organised and initially stunned the authorities. All three were arrested and jailed and persecuted. Although the strike effectively lasted for at least three years, it never officially ended. But the strike was about much more than 30/- a week wages and better conditions. They began agitating for rights, dignity and proper entitlements in their own country.

In order to survive away from the stations, The Mob established their own camps and traded kangaroo and goat skins. Initially under Don McLeod’s direction, they began alluvial mining with yandys until they could afford equpment. Ironically, their succesful mining operations drew attention to the mineral wealth of the Pilbara. They supported themselves this way for over 20 years, acquired three stations, established schools and began developing a way of life based on Aboriginal communal organisation.

The Mob had solid supporters like the Communist Party, some of the churches, womens groups and a small group of artists. The Fremantle branch of the Seamen's Union refused to load the squatters wool on boats while the strike was on and eventually the Australian Workers Union supported the Mobs claims for wages and better conditions.

When Western Australia was first established as a State by the settlers, the constitution made provision for a small percentage of State revenue to be allocated for Aboriginal people. McLeod turned bush lawyer and went on to argue that this had been illegally changed and continued to agitate for restitution for the West’s Aboriginal population.

He also went on to support other actions for justice for Aboriginal people, including the fight against oil drilling on Aboriginal land at Noonkanbah in the Kimberley region of WA in the late 1970s.

At one level the strike collapsed, but like the Eureka Stockade, it was a victory won from a battle lost. Many gains were made. There are so many characters in this heroic story that this song is not enough to give a full picture of the remarkable efforts by a small group of disempowered people. There was Peter Coppin, the songman Donald Norman, Daisy Bindi, Ernie Mitchell and so many more heroes of this struggle and they can take credit for giving birth to the Aboriginal Land Rights movement and inspiring the Gurindji walk off at Wave Hill in the 1960’s.

In the foreword to Max Brown’s book, Black Eureka, the writer Dorothy Hewett wrote, “A little mob of Nor’-West Aborigines without status, funds, or human rights, challenged the feudal strongholds of squatters, missions, courts, newspaper barons and governments, all the way up to the United Nations. It is a classic story of the underdog and his uncountable resources. It records the birth of the militant Aboriginal movement and it is part of Australian history now.”

This is one of the remarkable stories of Australian history that should be taught to our school children, as a chapter we should never forget. Remember.

Shane Howard

.......................

Shane Howard occupies a place of honour in the struggle for a progressive Australian culture. His early albums with the band Goanna took up democratic and indigenous themes and expressed them through a distinctively Australian-sounding musical ambience.

Defying the racist Howard (ie John) Government's dismissal of progressive histories that revealed the truth of the violent colonial dispossession of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as a "black armband" view of history, Howard (ie Shane) created the Black Arm Band Ensemble, travelling to world festivals, most of Australia’s major arts festivals and into remote and regional Aboriginal communities, helping to take the ensemble’s musical message of hope. He produced Archie Roach’s last studio album, Journey and collaborated with the young Street Warriors and Shannon Noll for a new, Hip Hop version of Solid Rock. For 30 years Howard has eloquently pleaded the case for Aboriginal justice.

Defying the racist Howard (ie John) Government's dismissal of progressive histories that revealed the truth of the violent colonial dispossession of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as a "black armband" view of history, Howard (ie Shane) created the Black Arm Band Ensemble, travelling to world festivals, most of Australia’s major arts festivals and into remote and regional Aboriginal communities, helping to take the ensemble’s musical message of hope. He produced Archie Roach’s last studio album, Journey and collaborated with the young Street Warriors and Shannon Noll for a new, Hip Hop version of Solid Rock. For 30 years Howard has eloquently pleaded the case for Aboriginal justice.

Defying the racist Howard (ie John) Government's dismissal of progressive histories that revealed the truth of the violent colonial dispossession of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as a "black armband" view of history, Howard (ie Shane) created the Black Arm Band Ensemble, travelling to world festivals, most of Australia’s major arts festivals and into remote and regional Aboriginal communities, helping to take the ensemble’s musical message of hope. He produced Archie Roach’s last studio album, Journey and collaborated with the young Street Warriors and Shannon Noll for a new, Hip Hop version of Solid Rock. For 30 years Howard has eloquently pleaded the case for Aboriginal justice.

Defying the racist Howard (ie John) Government's dismissal of progressive histories that revealed the truth of the violent colonial dispossession of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as a "black armband" view of history, Howard (ie Shane) created the Black Arm Band Ensemble, travelling to world festivals, most of Australia’s major arts festivals and into remote and regional Aboriginal communities, helping to take the ensemble’s musical message of hope. He produced Archie Roach’s last studio album, Journey and collaborated with the young Street Warriors and Shannon Noll for a new, Hip Hop version of Solid Rock. For 30 years Howard has eloquently pleaded the case for Aboriginal justice.Last year he returned to Uluru to work with the school children from Mutitjulu, Imanpa and Docker River communities, to create illustrations for a soon to be released childrens book of Solid Rock, in English and Pijantjatjara.

In 2000 he was awarded a Fellowship by the Music Fund of the Australia Council in acknowledgement of his contribution to Australian musical life. During this Fellowship period he began researching and writing a screenplay based around the events that led to the Eureka Stockade. In 2004, he was a special guest at the ceremonies to mark the 150th anniversary of the Eureka Stockade, in Ballarat. The events of the Eureka Stockade are close to Howard's heart as his great Grandfather was arrested at the Stockade battle.

1 comment:

Have you ever read Voltairine De Cleyre's haymarket speech? I think you'd find it very interesting. http://www.luminist.org/archives/dawn_light.htm

Post a Comment